Calories in vs. out

This article is from our friends over at Precision Nutrition and is republished here with their permission. Check out the Precision Nutrition course!

“You’re either with me, or you’re against me.”

This kind of binary mindset does fuel plenty of heated debates. Especially when it comes to one topic in particular: “calories in vs. calories out,” or CICO.

CICO is an easy way of saying:

This is a fundamental concept in body-weight regulation, and about as close to scientific fact as we can get.

Then why is CICO the source of so much disagreement?

It’s all about the extremes. At one end of the debate, there’s a group who believes CICO is straightforward. If you aren’t losing weight, the reason is simple: You’re either eating too many calories, or not moving enough, or both. Just eat less and move more.

At the other end is a group who believes CICO is broken (or even a complete myth). These critics say it doesn’t account for hormone imbalances, insulin resistance, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and other health problems that affect metabolism. Some also claim that certain diets and foods provide a “metabolic advantage” that helps people lose weight without worrying about CICO.

Neither viewpoint is completely wrong. But neither is completely right, either. Whether you’re a health and exercise professional tasked with helping clients manage their weight—or trying to learn how to do that for yourself—adopting an extreme position on this topic is problematic; it prevents you from seeing the bigger picture.

This article adds some nuance to the debate.

I’ll start by clearing up some misconceptions about CICO, and then explore several real-world examples showing how extreme views can hold folks back.

Much of the CICO debate—as with many other debates—stems from misconceptions, oversimplifications and a failure (by both sides) to find a shared understanding of concepts. Let’s start by getting everyone on the same page.

CICO goes beyond food and exercise.

There’s an important distinction to be made between CICO and “eat less, move more,” but some tend to conflate the two.

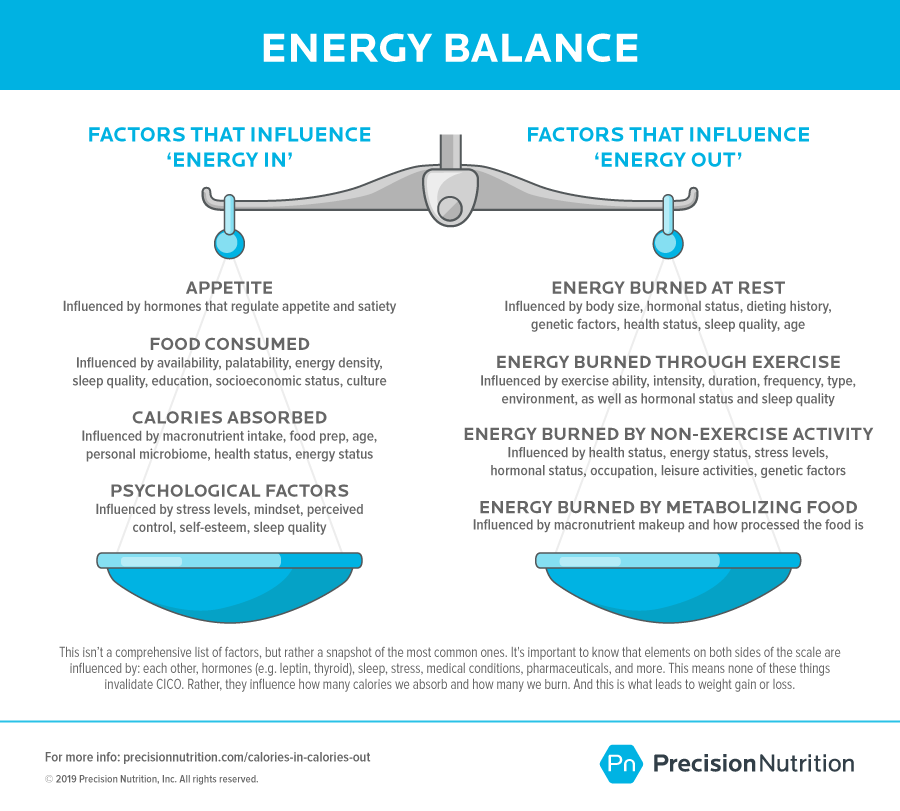

“Eat less, move more” only considers the calories you eat and the calories you burn through exercise and other daily movement. But CICO is really an informal way of expressing the Energy Balance Equation, which is far more involved.

The Energy Balance Equation—and therefore CICO—includes all the complex inner workings of the body, as well as the external factors that ultimately impact “calories in” and “calories out.”

Imperative to this, and often overlooked, is your brain. It’s constantly monitoring and controlling CICO. Think of it as mission control, sending and receiving messages that involve your gut, hormones, organs, muscles, bones, fat cells, external stimuli (and more) to help balance “energy in” and “energy out.”

It’s a complicated—and beautiful—system. Yet the Energy Balance Equation itself looks really simple:

[Energy in] – [Energy out] = Changes in body stores*

With this equation, “energy in” and “energy out” aren’t just calories from food and exercise. As you can see in the illustration below, all kinds of factors influence these two variables.

When you view CICO through this lens—by zooming out for a wider perspective—you can see boiling it down to “eat less, move more” is a significant oversimplification.

Many people use calorie calculators to estimate their energy needs and to approximate how many calories they’ve eaten. But these tools don’t always work. As a result, people start to question whether CICO is broken. The keywords here are “estimate” and “approximate” because calorie calculators aren’t necessarily accurate.

For starters, they provide an output based on averages and can be off by as much as 20 to 30% in normal, young, healthy people. They may vary even more in older, clinical or individuals with obesity.

And that’s just on the “energy out” side. The number of calories you eat—or your “energy in”—is also just an estimate. For example, the FDA allows inaccuracies of up to 20% on label calorie counts, and research shows restaurant nutrition information can be off by 100-300 calories per food item.

What’s more, even if you were able to accurately weigh and measure every morsel you eat, you still wouldn’t have an exact “calories in” number because there are other confounding factors, such as:

Of course, this doesn’t mean CICO doesn’t work. It only means the tools we use to estimate “calories in” and “calories out” are limited.

To be crystal clear: Calorie calculators can still be very helpful for some people, but it’s important to be aware of their limitations. If you’re going to use one, do so as a rough starting point, not a definitive “answer.”

CICO doesn’t require calorie counting.

At Precision Nutrition, sometimes we use calorie counting to help clients improve their food intake. Other times we use hand portions. And other times we use more intuitive approaches.

For example, let’s say a client wants to lose weight, but they’re not seeing the results they want. If they’re counting calories or using hand portions, we might use those numbers as a reference to further reduce the amount of food they’re eating. But we also might encourage them to use other techniques, such as eating slowly or until they’re 80% full.

In every case—whether we’re talking numbers or not—we’re manipulating “energy in.” Sometimes directly and sometimes indirectly. So, make no mistake: Even when we’re not “counting calories,” CICO still applies.

CICO might sound simple, but it’s not.

There’s no getting around it: If you (or a client) aren’t losing weight, you either need to decrease “energy in” or increase “energy out.” But as you’ve already seen, that may involve far more than just pushing away your plate or spending more time at the gym.

For instance, it may require you to:

Sometimes the solutions are obvious; sometimes they aren’t. But with CICO, the answers are there, if you keep your mind open and examine every factor.

Imagine yourself as a “calorie conductor” who oversees and fine-tunes many actions to create metabolic harmony. You’re looking for anything that could be out of sync. This takes lots of practice.

To help, here are five common energy balance dilemmas. In each case, it might be tempting to assume CICO doesn’t apply, but look a little deeper, and you’ll see the principles of CICO are always present.

5 Common Energy Balance Dilemmas

Can you guess what happened?

More than likely, “energy in” or “energy out” did change, but in a way that felt out of control or unnoticeable.

The culprit could be:

In all these cases, CICO is still valid. Energy balance just shifted in subtle ways, due to lifestyle and health status changes, making it hard to recognize.

Hormones seem like a logical scapegoat for weight changes.

And while they’re probably not to blame as often as people think, hormones are intricately entwined with energy balance.

Even so, they don’t operate independently of energy balance. People gain weight because their hormones are impacting their energy balance, which often happens during menopause or when thyroid hormone levels decline.

For example, triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) are two thyroid hormones that are incredibly important for metabolic function. If levels of these hormones diminish, weight gain may occur. But this doesn’t negate CICO: Your hormones are simply influencing “energy out.”

This may seem a bit like splitting hairs, but it’s an important connection to make, whether we’re talking about menopause or thyroid problems or insulin resistance or other hormonal issues.

Understanding that CICO is the true determinant of weight loss means that you have many more tools for achieving the outcome you want.

Suppose you’re working from the false premise that hormones are the only thing that matters. This can lead to increasingly unhelpful decisions, such as spending a large sum of money on unnecessary supplements or adhering to an overly restrictive diet that backfires in the long run.

Instead, you know results are dependent on the fact that “energy in” or “energy out” has changed. Now, this change can be due to hormones, and if so, you’ll have to adjust your eating, exercise and/or lifestyle habits to account for it. (This could include taking medication prescribed by your doctor, if appropriate.)

Research suggests people with mild (10-15% of the population) to moderate hypothyroidism (2-3%) may experience a metabolic slowdown of 140 to 360 calories a day. This amount can be enough to lead to weight gain or make it harder to lose weight. (One caveat: Mild hypothyroidism can be so mild many people don’t experience a significant shift in metabolic activity, making it a non-issue.)

What’s more, women suffering from polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS (about 5-10%), and those going through menopause may also experience hormonal changes that disrupt energy balance.

It’s important to understand your (or your client’s) health status, as that will provide valuable information about the unique challenges involved and how you should proceed.

So what gives? The conclusion most people jump to: Their metabolism is broken. They’re broken. And CICO is broken.

But here’s the deal: Metabolic damage isn’t really a thing. Even though it may seem that way.

While an energy balance challenge could be related to a hormonal issue, as discussed above, when someone’s eating 1,000 calories a day but not losing weight, it’s usually due to one of the two reasons that follow.

(No matter how simple they sound, this is what we’ve seen repeatedly in our coaching program, with more than 100,000 clients.)

It’s easy to miscalculate how much you’re eating, as it’s usually unintentional. The most typical ways people do it:

A landmark study, and repeated follow-up studies, have found people often underestimate how much they eat over the course of a day, sometimes by more than 1,000 calories.

I’m not suggesting it’s impossible to be realistic about portion sizes, but if you (or your clients) aren’t seeing results on a low-calorie diet, it’s worth considering that underestimation may be the problem.

Workweeks can be stressful and when Friday night rolls around, people put their guard down and let loose. (You probably can’t relate, but just try, O.K.?)

Here’s how it goes: Let’s say a person is eating 1,500 calories a day on weekdays, which would give them an approximate 500-calorie deficit.

But on the weekends, they deviate from their plan just a little:

The final tally: An extra 4,000 calories consumed between Friday night and Sunday afternoon. They’ve effectively canceled out their weekday deficit, bumping their average daily calories to 2,071.

The upshot: If you (or your client) have slashed your calories dramatically, but aren’t seeing the expected results, look for the small slips. It’s like being a metabolic detective who’s following—perhaps literally—the breadcrumbs.

By the way, if downtime is a problem for you (or a client), here’s the remedy: 5 surprising strategies to ditch weekend overeating.

This might be the top reason some people reject CICO. Say someone switches from a diet of mostly processed foods to one made up of mostly whole, plant-based foods. They might find they can eat as much food as they want, yet the pounds still melt away. People often believe this is due to the “power of plants.”

Yes, plants are great, but this doesn’t disprove energy balance. Because plant foods have a very low energy density, you can eat a lot of them and still be in a calorie deficit. Especially if your previous intake was filled with lots of processed, hyper palatable “indulgent foods.”

It feels like you’re eating much more food than ever before—and, in fact, you really might be. On top of that, you might also feel more satiated because of the volume, fiber, and water content of the plants. All of which is great, but it doesn’t negate CICO.

Or take the ketogenic diet, for example. Here, someone might have a similar experience of “eating as much as they want” and still losing weight, but instead of plant foods, they’re eating meat, cheese and eggs. Those aren’t low-calorie foods, and they don’t have much fiber, either. As a result, plenty of low-carb advocates claim keto offers a “metabolic advantage” over other diets.

Here’s what’s most likely happening:

For these reasons, people tend to eat fewer calories and feel less hungry.

Although it might seem magical, the keto diet results in weight loss by regulating “energy in” through a variety of ways.

You might ask: If plant-based and keto diets work so well, why should anyone care if it’s because of CICO, or for some other reason?

Depending on the person—food preferences, lifestyle, activity level, and so on—many diets, including plant-based and keto, aren’t sustainable long-term. This is particularly true of the more restrictive approaches.

And if you (or your client) believe there’s only one “best diet,” you may become frustrated if you aren’t able to stick to it. You may view yourself as a failure and decide you lack the discipline to lose weight. You may even think you should stop trying. None of which are true.

Your results aren’t diet dependent. They’re behavior dependent.

Maintaining a healthy body (including a healthy body weight) is about developing consistent, sustainable daily habits that help you positively impact “energy in” and “energy out.”

This might be accomplished while enjoying the foods you love, by:

It’s about viewing CICO from 30,000 feet and figuring out what approach feels sane—and achievable—for you.

Sure, that might include a plant-based or keto diet, but it absolutely might not, too. And you can get great results either way.

The CICO conversation doesn’t always revolve around weight loss. Some people struggle to gain weight, especially younger athletes and people who are very active at work (think: jobs that involve manual labor).

It also happens with those who are trying to regain lost weight after an illness.

When someone intentionally eats more food but can’t pack on the pounds, it may seem like CICO is invalidated, but here’s what our coaches have found:

People tend to remember extremes.

Someone might have had six meals in one day, eating as much as they felt like they could stand, but the following day, they only ate two meals because they were still so full. Maybe they were busy, too, so they didn’t even think much about it. The first day—the one where they stuffed themselves—would likely stand out a lot more than the day they ate in accordance with their hunger levels. That’s just human nature.

It’s easy to see how CICO is involved here. It’s a lack of consistency on the “energy in” part of the equation.

One solution: Instead of stuffing yourself with 3,000 calories one day, and then eating 1,500 the next, aim for a calorie intake just above the middle that you can stick with, and increase it in small amounts over time, if needed.

People often increase activity when they increase calories.

When some people suddenly have more available energy—from eating more food—they’re more likely to do things that increase their energy out, such as taking the stairs, pacing while on the phone and fidgeting in their seats.

They might even push harder during a workout than they would normally. This can be both subconscious and subtle.

And though it might sound weird, our coaches have identified this as a legitimate problem for “hard gainers.”

Your charge: Take notice of all your activity. If you can’t curtail some of it, you may have to compensate by eating even more food. Nutrient- and calorie-dense foods such as nut butters, whole grains and oils can help, especially if you’re challenged by a lack of appetite.

Once you accept that CICO is both complex and inescapable, you may find yourself up against one very common challenge, namely: “I can’t eat any less than I am now!” This is one of the top reasons people abandon their weight-loss efforts or go searching in vain for a miracle diet.

Here are three simple strategies you (or your clients) can use to create a caloric deficit, even if it seems impossible. It’s all about figuring out which one works best for you.

Consuming higher amounts of protein increases satiety, helping you feel more satisfied between meals. And consuming higher amounts of fiber increases satiation, helping you feel more satisfied during meals. These are both proven in research and practice to help you feel more satisfied overall while eating fewer calories, leading to easier fat loss.

While the advice to eat more protein and fiber may sound trite, most people trying to lose weight still aren’t focused on getting plenty of these two nutrients.

And you know what? It’s not their fault. When it comes to diets, almost everyone has been told to subtract, to take away the “bad” stuff and only eat the “good” stuff.

But there’s another approach: Just start by adding. If you make a concerted effort to increase protein (especially lean protein) and fiber intake (especially from vegetables), you’ll feel more satisfied. You’ll also be less tempted by all the foods you think you should be avoiding, which helps to automatically “crowd out” ultra-processed foods.

Which leads to another big benefit: By eating more whole foods and fewer of the processed kind, you’re actually retraining your brain to desire those indulgent, ultra-processed foods less.

That’s when a cool thing happens: You start eating fewer calories without actively trying to—rather than purposely restricting because you have to. This makes weight loss easier.

Starting is simple: For protein, add one palm-sized portion of relatively lean protein—chicken, fish, tempeh—to one meal. This is beyond what you would have had otherwise. Or have a Super Shake as a meal or snack.

For fiber, add one serving of high-fiber food, such as vegetables, fruit, lentils and beans, to your regular intake. This might mean having an apple for a snack, including a fistful of roasted carrots at dinner, or tossing in a handful of spinach in your Super Shake.

Try this for two weeks, and then add another palm of lean protein, and one more serving of high-fiber foods.

In addition to all the upside we’ve discussed so far, there’s also this: Coming to the table with a mindset of abundance—rather than scarcity—can help you avoid those anxious, frustrated feelings that often come with being deprived of the foods you love. So instead of saying, “Ugh, I really don’t think I can give up my nightly wine and chocolate habit,” you might say, “Hey, look at all this delicious, healthy food I can feed my body!”

(And by the way, you don’t have to give up your wine and chocolate habit, at least not to initiate progress.)

Imagine you’re on vacation and you slept in and missed breakfast. Of course, you don’t really mind because you’re relaxed and having a great time. And there’s no reason to panic: Lunch will happen.

But since you’ve removed a meal, you end up eating a few hundred calories less than normal for the day, effectively creating a deficit. Given that you’re in an environment where you feel calm and happy, you hardly even notice.

Now suppose you wake up on a regular day, and you’re actively trying to lose weight. You might think: “I only get to have my 400-calorie breakfast, and it’s not enough food. This is the worst. I’m going to be so hungry all day!” You head to work feeling stressed, counting down the minutes to your next snack or meal. Maybe you even start to feel deprived and miserable.

Here’s the thing: You were in a calorie deficit both days, but your subjective experience of each was completely different.

What if you could adjust your thinking to be more like the first scenario rather than the second?

Of course, I’m not suggesting you skip breakfast everyday (unless that’s just your preference). But if you can manage to see eating less as something you happen to be doing— rather than something you must do—it may end up feeling a lot less terrible.

Are you a person who doesn’t want to eat less, but would happily move more? If so, you might be able to take advantage of something I’ve called G-Flux.

G-Flux, also known as “energy flux,” is the total amount of energy that flows in and out of a system.

As an example, say you want to create a 500-calorie deficit. That could look like this:

But it could also look like this:

In both scenarios, you’ve achieved a 500-calorie deficit, but the second allows you to eat a lot more food. That’s one benefit of a greater G-Flux.

But there’s also another: Research suggests if you’re eating food from high-quality sources and doing a variety of workouts—strength training, conditioning and recovery work—eating more calories can help you carry more lean mass and less fat because the increased exercise doesn’t just serve to boost your “energy out.” It also changes nutrient partitioning, sending more calories toward muscle growth and fewer to your fat cells.

Plus, since you’re eating more food, you have more opportunity to get the quantities of vitamins, minerals and phytonutrients you need to feel your best.

To be clear, this is a somewhat advanced method. And because metabolism and energy balance are dynamic in nature, the effectiveness of this method may vary from person to person. Plus, not everyone has the ability or the desire to spend more time exercising. And that’s O.K.

By being flexible with your thinking—and willing to experiment with different ways of influencing CICO—you can find your own personal strategy for tipping energy balance in your (or your clients’) favor.

.jpg)

Qatar Secures Place Among the World's Top 10 Wealthiest Nations

.jpg)

Hamad International Airport Witnesses Record Increase in Passenger Traffic

Saudi Arabia: Any visa holder can now perform Umrah

What are Qatar's Labour Laws on Annual Leave?

Leave a comment